The Evolution of Community Bank Business Model Series: Rural Banks Endure in the Face of Challenges

The Evolution of the Community Bank Business Model series1 concludes with this article that focuses on how urban and rural banks have been influenced by changes in the banking environment.2 Some changes have uniformly affected both rural and urban banks. From 2015 to 2019, for instance, rural community banks decreased in number by 14 percent, while urban community banks decreased in number by 17 percent — a relatively modest difference in rates of contraction.3 A similar story emerges from comparisons of profitability, as returns on assets from 2015 to 2019 were higher at rural banks than at urban banks in some years and lower in others.4

However, other changes in the banking environment have affected urban and rural banks differently. This article focuses on the following six differences: lending specialization, branching, competition, small business lending, managerial succession, and technology. These are not inclusive or thoroughly analyzed in a way that accounts for variation in size across banks in urban and rural markets. Nevertheless, they are important, both individually and collectively, in demonstrating how rural community banks remain competitive in today’s banking environment.

Lending Specialization

Lending specialization is important in understanding community banks, as risks and returns vary by loan type, time period, and degree of diversification.5 They also vary by urban and rural location.

Urban banks are more concentrated in commercial real estate lending. This lending specialty was relatively unprofitable prior to the Great Recession and relatively profitable afterward.6 Rural banks are more concentrated in agricultural lending (Figures 1 and 2), which has been a relatively profitable specialization for decades.7 Other concentrations are more similarly distributed for urban banks and rural banks.

Figure 1: Percentage of Urban Banks with Assets Under $10 Billion, Specialized by Loan Type

Source: Call Report data. The numbers represent the percentages of community banks specializing in various lending categories.

Figure 2: Percentage of Rural Banks with Assets Under $10 Billion, Specialized by Loan Type

Source: Call Report data. The numbers represent the percentages of community banks specializing in various lending categories.

Looking at changes over time, the percentages of banks specializing in the various forms of lending have generally increased by amounts that are modest in raw percentages but, in some cases, represent large proportions relative to initial levels. These changes, however, do not appear to be markedly and systematically different across rural and urban locations. This contrasts with earlier findings that urban banks were more likely to change specializations than rural banks.8

Branching

Branching activity is important both as a method of delivery for financial services and as a scale by which endurance can be weighed. The balance appears to favor rural banks (Table 1). In 2019, for instance, 1,540 branches closed in urban areas compared with 98 in rural areas. Ratios of closed to total branches follow a similar pattern, at levels of 0.14 percent in rural areas and 2.21 percent in metropolitan areas. Although rural branch closures are less common than urban branch closures, they may be more impactful because rural customers have fewer alternative services than customers in urban areas.

Table 1: Branch Closings, 2015 to 2019

Note: The sample consists of full-service brick-and-mortar bank branches operating outside main offices. Closings for a given year occur during the one-year period ending on June 30 of that year. The ratio of closed branches to total branches is calculated as the number of branches that closed within that year divided by the number of branches in existence at the beginning of the year. Rural banks are those located outside metropolitan or micropolitan statistical areas. Urban branches are in metropolitan statistical areas.

Source: FDIC Summary of Deposits data

Market Concentration

More competition helps consumers by encouraging greater product differentiation, a lowering of the cost of financial intermediation, and more access to financial services.9 It can hurt banks to the extent that it leads to lower net interest margins (lower interest rates on loans and higher interest rates on deposits). It also may foster excessive risk taking and thereby lead to a less stable banking environment.10 Regulators balance these factors in monitoring banking market structure.

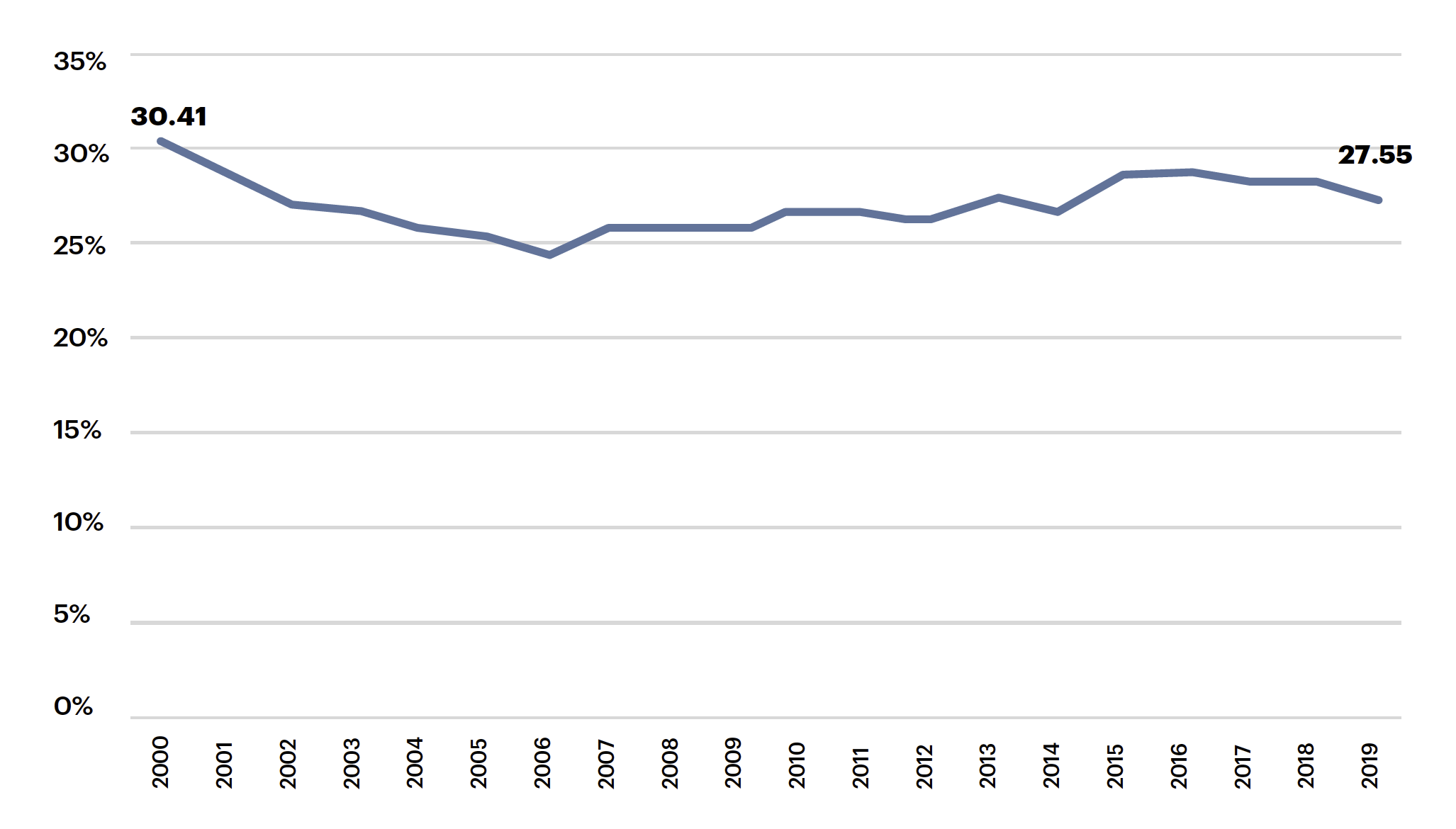

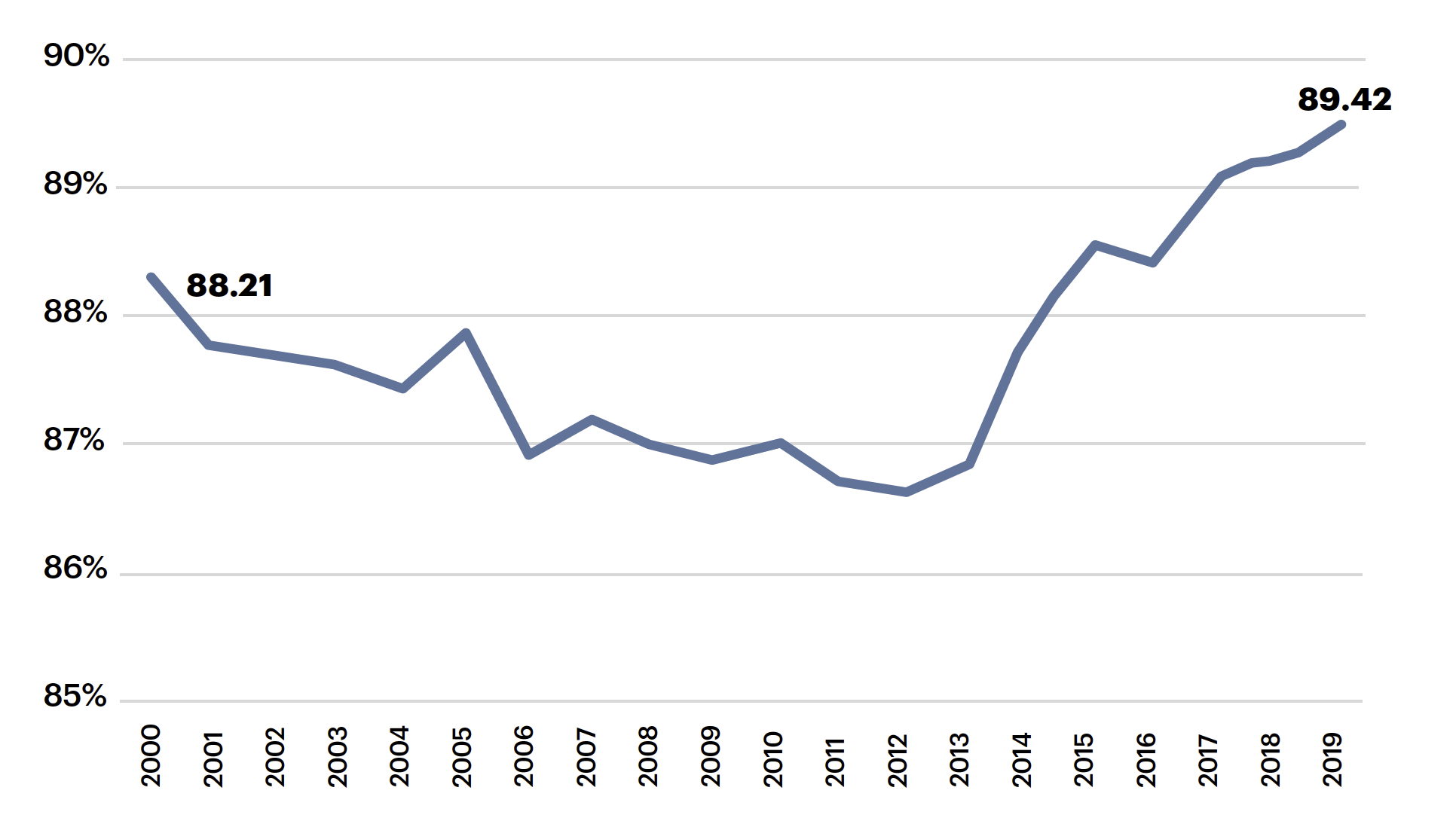

Rural banks operate in more concentrated markets than urban banks.11 In 2019, for instance, less than 28 percent of the banks in urban markets (Figure 3) operated in markets considered to be highly concentrated, compared with about 89 percent of the banks in rural markets (Figure 4). Moreover, this difference has become more pronounced over time. From 2000 to 2019, the number of rural banks in concentrated markets has increased (from 88 percent to 89 percent), while the number of urban banks has decreased (30 percent to 28 percent).

The foregoing analysis of market concentration shows that community banks in urban areas are subject to tougher competition, which, theoretically, lessens their influence over the pricing and provisioning of bank services in their markets. Rural banks, alternatively, experience less in-market competition for banking products and services.

Figure 3: Percent of Urban Markets with HHIs Greater Than 1,800

Source: FDIC Summary of Deposits data

Figure 4: Percent of Rural Markets with HHIs Greater Than 1,800

Source: FDIC Summary of Deposits data

Small Business Lending

Small business lending often is described as the hallmark of community banking. But this traditional role has been challenged by non–community banks as well as by other lenders. For example, from 2015 to 2019, loans to small businesses as percentages of assets at community banks declined by 8 percent while increasing by 4 percent at non–community banks.12

Rural banks, however, were less impacted than urban banks (see Table 2). Loans to small businesses, expressed both in dollar volumes and as percentages of assets, were relatively stable from 2015 to 2019 for rural banks, while declining for urban banks. This may indicate an evolution in banking that varies by geographic location, with rural banks maintaining a more traditional banking model.

Table 2: Small Loans to Businesses at Community Banks

Source: Call Report data. Dollar amounts are expressed in billions.

Succession

Rural banks are often said to be challenged by difficulties in attracting qualified managers. Some analysts have contended that if talent is correlated with performance and is less accessible in rural communities, then difficulty in replacement of managers at rural banks, compared with equivalent replacement at urban banks, could, over time, erode their competitiveness. Evidence in support of this contention, however, is anecdotal rather than empirical. A 2018 study that directly examined differences in performance between urban and rural banks when new chief executive officers came on board13 found that the competitiveness of rural banks is not, in fact, eroded by succession problems.

Technological Innovation

The introduction of new technologies historically has been slower in rural banking markets than in urban banking markets. This may be related, in part, to disinterest among rural populations, or lesser access to internet services, which, in 2015, were used by 75 percent of urban populations but by only 69 percent of rural populations.14 “We have approximately 4,000 separate customers using 16,000 loan and deposit accounts,” noted one banker in response to the Conference of State Bank Supervisors 2020 National Survey of Community Banks.15 “Yet, we have less than 500 users of our mobile banking app.”

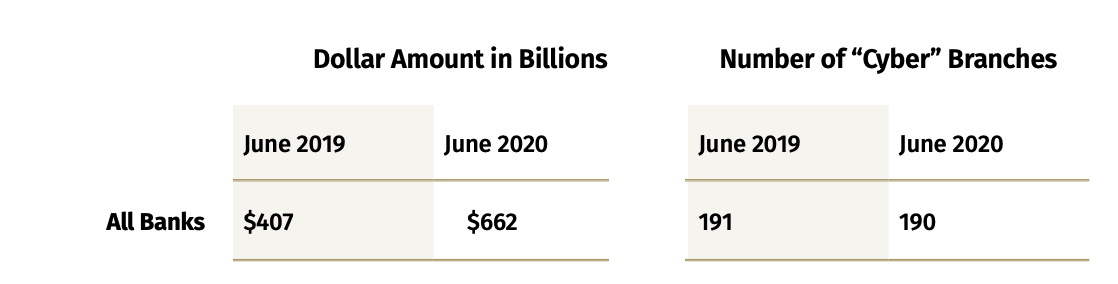

Another problem may reflect difficulties in supply, rather than demand, in technological services — that is, the limited operational capabilities of small, rural banks may be important, as well as the preferences of rural bank customers. In this regard, consider the tiny, but growing, use of internet deposits (Table 3), almost all of which were raised by non–community banks operating in urban areas. Rural banks, perhaps, could seek to access such out-of-market deposit gathering strategies as a possible response to locally contracting markets. They previously have been successful in introducing other technologies, including mobile banking and interactive teller machines.16

Table 3: Internet Deposits

Source: Call Report

Conclusion

Succession difficulties, limited loan demand, branch closures, and other factors that erode the competitiveness of rural banks are important, in part, because the loss of banking services is particularly impactful for customers in remote areas. However, the challenges facing rural community banks, compared with those in urban areas, may not be as stark as is sometimes suggested. They are doing better in small business lending, are not necessarily disadvantaged by succession, and are closing branches at lower rates. Their profitability approximates that of other banks, supported, perhaps, by advantages of operating in more concentrated markets. In some cases, community banks are overcoming technological limitations by adding new products and services. They have grown more similar to urban banks in how they change lending specializations.

Despite a more challenging economic environment, as stated in a 2018 speech by then Vice Chair for Supervision Randal K. Quarles, “rural community banks appear to be holding their own relative to urban community banks.”17

- 1 This article is the second in a two-part series based on research conducted in 2019 by Federal Reserve staff: Bettyann Griffith, Federal Reserve Bank of New York; Deeona Deoki, Federal Reserve Bank of New York; Chris Henderson, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia; Chantel Gerardo, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia; James Fuchs, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; Mark Medeiros, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta; Justin Reuter, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City; Jonathan Rono, Board of Governors; and James Wilkinson, retired from the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. The first article, “The Evolution of the Community Bank Business Model Series: Impact of Technology,” appeared in the Third Issue 2021 of Community Banking Connections and is available at www.cbcfrs.org/articles/2021/i3/the-evolution-of-the-community-bank-business-model-series-impact-of-technology.

- 2 For purposes of this analysis, “rural” community banks are located outside, and “urban” community banks are located inside metropolitan statistical areas.

- 3 Data were obtained from the Consolidated Reports of Condition and Income (Call Reports).

- 4 Data are from the Call Reports.

- 5 Specialization is measured using the methodology from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) Community Bank Study (2012) to categorize banks as specialists in mortgages, consumer loans, commercial real estate loans, agricultural loans, or business loans or as multi-specialists that focus on more than one category. The study is available at www.fdic.gov/regulations/resources/cbi/report/cbsi-execsumm.pdf.

- 6 FDIC Community Bank Studies (2012 and 2020).

- 7 FDIC Community Bank Studies (2012 and 2020).

- 8 FDIC Community Bank Study (2012).

- 9 A. Demirguc-Kunt, “Bank Concentration, Competition, and Financial Stability: What Are the Trade-Offs?” World Bank Blogs, May 11, 2010, available at https://blogs.worldbank.org/allaboutfinance/bank-concentration-competition-and-financial-stability-what-are-trade-offs.

- 10 See Demirguc-Kunt, “Bank Concentration, Competition, and Financial Stability: What Are the Trade-Offs?,” 2010.

- 11 A banking market with a Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) greater than 1,800 is considered by the U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Reserve System to be “highly concentrated.” For the definition of HHI, an explanation of how HHI is calculated, and the use of the index to assess market concentration, see “The ABCs of HHI: Competition and Community Banks,” On the Economy blog, St. Louis Fed, June 11, 2018, available at www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2018/june/hhi-competition-community-banks.

- 12 Data were obtained from the Consolidated Reports of Condition and Income (Call Reports).

- 13 D. Dahl, M. Milchanowski, and D. Coster, “CEO Succession and Performance at Rural Banks,” presented at the 2018 Community Banking in the 21st Century research and policy conference, available at www.communitybanking.org/~/media/files/communitybanking/2018 papers/session3_paper1_milchanowski.pdf.

- 14 D. Dahl, A. Meyer, and N. Wiggins. “How Fast Will Banks Adopt New Technology This Time?” Regional Economist, Fourth Quarter 2017, available at www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/fourth-quarter-2017/banks-adoption-fintech.

- 15 Results of the survey were presented at the 2020 Community Banking in the 21st Century research and policy conference. See www.csbs.org/system/files/2020-09/cb21publication_2020.pdf.

- 16 Conference of State Bank Supervisors 2020 National Survey of Community Banks.

- 17 See the October 4, 2018, speech, “Trends in Urban and Rural Community Banks” at the Community Banking in the 21st Century research and policy conference. A video of the speech. is available at www.communitybanking.org/video/brightpop/fc63e5dfc02240bfb9537202032ec2b2.