Loan and OREO Accounting Guidance ... for the Good Times

by Tim Melrose, Senior Examiner, and Kinney Misterek, Assistant Vice President, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis

Banks are beginning to experience general improvement in the overall credit quality of their loan portfolios. When the credit crisis began, many bankers were confronted with accounting challenges that they may not have had to deal with for some time. For example, some bankers were unfamiliar with the accounting requirements governing other real estate owned (OREO) because they seldom held OREO prior to the crisis. Similarly, bankers are now confronted with accounting issues related to various improving credit events that they may not have experienced in the recent past. These events include:

- returning a nonaccrual loan to accrual status;

- selling OREO; and

- evaluating troubled debt restructurings (TDRs).

To facilitate compliance, this article provides a basic overview of some of the more common accounting questions that arise as credit quality begins to improve. Although specific resources for more detailed guidance are included in this article, bankers may also want to seek their accountants' advice.

Returning a Nonaccrual Loan to Accrual Status

Regulatory guidance permits nonaccrual assets to be returned to accrual status under appropriate circumstances. A good resource for this process is the "Nonaccrual Status" entry in the Glossary of the "Instructions for Preparation of Consolidated Reports of Condition and Income (FFIEC 031 and 041)" (Call Report Glossary).1 The Call Report Glossary describes two primary options to return a nonaccrual loan to accrual status (there are additional options detailed within this section of the Call Report Glossary for accrual accounting and the restoration to accrual status for formally restructured loans, but they are beyond the scope of this article).

The first option requires that none of the loan's principal and interest (P&I) are due and unpaid and that the bank expects full repayment of the remaining contractual P&I. This option is met when a borrower brings all past due payments current. Additionally, a borrower can satisfy this option even when all past due payments have not yet been brought current as long as the borrower has resumed paying the full amount of the scheduled P&I payments and there is a sustained period of repayment performance (generally a minimum of six months) and reasonable assurance that all P&I contractually due, including any arrearages, will be collected in a reasonable period. For loans with interest-only payments or payments due less than monthly (that is, semiannually or annually), banks should perform a credit analysis and clearly document the timely collectibility of all contractually required payments prior to returning the loan to accrual status.

The second option requires that the loan be well secured and in the process of collection. This condition is typically met when the bank is reasonably certain that collection efforts, including legal action, will result in repayment of the debt or restoration to current status within a short period of time, generally within 30 to 90 days. Simply commencing collection efforts does not constitute "in the process of collection."

One item not discussed in detail in U.S. generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) or the Call Report Glossary is the "cost recovery method." This entails accounting for restoring a nonaccrual loan to accrual status when interest payments have been applied to the principal while the loan is in nonaccrual status because of doubt about the collectibility of the recorded principal. The Call Report Glossary instructions state that interest payments that were applied to reduce the principal should not be reversed when returning the asset to accrual status. When the loan returns to accrual status, an acceptable method would be to recognize interest income based on the new effective yield to maturity on the loan.

For example, assume that a loan with a remaining balance of $100,000, a 4 percent fixed rate, and five years remaining before it becomes fully amortized at $1,841 P&I per month is moved to nonaccrual status. The loan is held in nonaccrual status for 12 months. Assume further that the bank uses the cost recovery method (described in further detail on page 20) and the borrower makes all scheduled payments while the loan is in nonaccrual status. Because of doubt about the collectibility of the recorded principal, 12 payments of $1,841 are applied to reduce the principal from $100,000 to $77,908. At the end of 12 months, the bank confirms that the loan satisfies the requirements discussed above to restore the loan to accrual status.

The $100,000 loan would reflect the principal reduction of $22,092, leaving a net loan balance of $77,908, with a remaining four years of monthly payments at $1,841. The bank would calculate a new yield based on the remaining loan balance, maturity, and scheduled payments to determine the allocation of future payments between the principal and the interest. In this case, the yield is adjusted from 4 percent to 6.32 percent. Amortization of the first monthly payment made is applied as follows: $341 to the interest and $1,500 to the principal.

While this example is relatively simple, it illustrates an important concept. Because regulatory reporting instructions do not allow payments that were applied to reduce the principal to be reversed, the restoration accounting and the change in yield calculation can be complex.

Selling OREO

Accounting for the sale of OREO can be challenging when the bank finances the sale. Proper accounting for the sale of OREO is detailed in the "Foreclosed Assets" entry of the Call Report Glossary. In addition, Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) 360-20 is the primary accounting guidance for the sale of any bank property, plant, or equipment. GAAP permit five different accounting methods when a bank finances the disposition of its own OREO: the full accrual, installment, reduced-profit, cost recovery, and deposit methods. Which method is appropriate in a specific case depends on all the facts and circumstances surrounding the sale.

While many banks commonly use either the full accrual or installment method to account for OREO dispositions that they finance, the primary considerations for determining the accounting method to be used are the buyer's "initial investment" (that is, the down payment) and his or her "ongoing investment" (that is, the required amortization schedule). Specifically, the use of the full accrual method is allowed if:

- the sale is consummated;

- the buyer's initial and ongoing investments are adequate to demonstrate a commitment to pay for the property (refer to ASC 360-20-55 for qualifications for using this method, including the minimum down payment based on the type of real estate financed);

- the receivable is not subject to future subordination; and

- the usual risks and rewards of ownership have been transferred, including the bank no longer having a substantial continuing involvement in the property.

Using the full accrual method allows the bank to recognize the sale, the corresponding new loan, and any gain at the time of sale. Any loss from the sale of OREO must be recognized immediately.

Other methods may be used when the transaction cannot meet certain conditions prescribed under the full accrual method. For instance, if the buyer's initial investment is not adequate under the full accrual method but the bank's ability to recover the cost of the property remains reasonably assured, the bank may use the installment method. This method recognizes the OREO sale and corresponding accrual loan. However, any gain from the sale will only be recognized as the bank receives payments (includes both initial and ongoing principal payments) from the buyer. A loss on a sale is always recognized immediately.

The following example illustrates the different accounting entries under these two approaches.

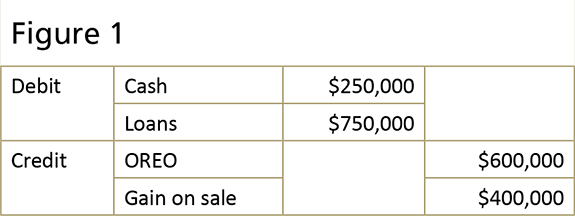

Assume a bank owns a hotel that is considered a start-up and the book value after write-downs is $600,000. The bank is financing the sale, and the property sells for $1,000,000, for a $400,000 gain. The buyer makes an adequate down payment (25 percent of the sales price for this type of property) of $250,000 and will repay the remaining balance on a 12-year amortization (a customary schedule for the type of property). At consummation, the transaction qualifies for full accrual treatment. The loan and gain on the sale are reflected on the bank's books as shown in Figure 1.

Future payments will be accounted for as amortizing P&I payments on the loan.

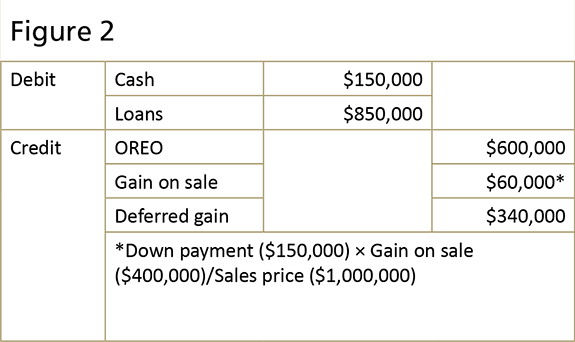

Now consider a scenario in which the buyer provides only a 15 percent down payment ($150,000), but recovery of the cost of the property is reasonably assured if the buyer defaults. Assuming the same amortization schedule, the bank would use the installment method, since the down payment for this type of property is not adequate. Using this method will delay full recognition of the gain until the down payment requirement is met. The entries are shown in Figure 2.

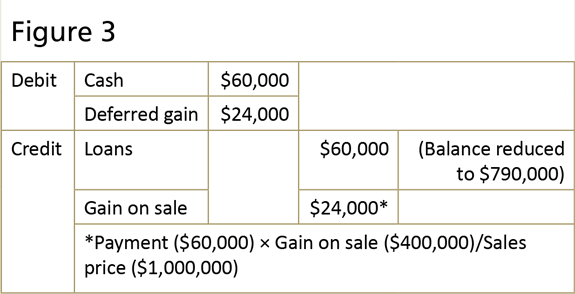

As future payments are made, all interest payments can be recognized as interest income (assuming the loan is at market rate)2 and a portion of the deferred gain can be recognized. For example, the entries in Figure 3 would be used if the borrower made a $60,000 principal reduction during the first year.

At some point, the buyer will have made payments that are sufficient to satisfy the down payment requirements. At that time, and assuming all other criteria are met, the bank may recognize the remaining deferred gain under the full accrual method.

While the full accrual and installment methods are more commonly used, a bank may also use the following methods when appropriate:

- The reduced-profit method, though seldom used, is similar to the installment method in accounting for the gain on sale. However, it is typically used when the down payment requirement is met, but the loan amortization schedule does not meet the full accrual method requirements.

- The cost recovery method is typically used when the sale does not qualify under the full accrual, installment, or reduced-profit method. If this method is used, no profit or interest income is recognized until either the buyer's aggregate payments exceed the seller's cost of the property sold or there is a change to another accounting method.

- The deposit method is used when a sale is not consummated. ASC 360-20-40-7 details that the following four conditions must be met for a sale to be consummated: 1) parties are bound by a contract, 2) consideration has been exchanged, 3) permanent financing has been arranged, and 4) all conditions precedent to closing the sale have been performed. Using this method, a bank does not recognize a sale, the asset remains in OREO, and no income or profit can be recognized. The deposit method can also be used for dispositions that could be accounted for under the cost recovery method.

Evaluating TDRs

Bankers have had many questions about the proper accounting treatment for TDRs. The banking regulatory agencies have emphasized that, if done prudently, loans modified in a TDR may be in the best interest of both the borrower and the bank. Regulatory sources also make clear that not all TDRs are "bad" loans. In fact, some TDRs can be maintained on accrual status at the time of modification.

Likewise, a TDR designation does not necessarily make the loan subject to an adverse classification. Regulators have issued interagency guidance to further clarify the accounting and classification treatment of both collateral- and non-collateral-dependent TDRs. Refer to SR letter 13-17, "Interagency Supervisory Guidance Addressing Certain Issues Related to Troubled Debt Restructurings."3 A detailed discussion of this guidance is beyond the scope of this article, but bankers with questions about TDRs are encouraged to review the guidance.

Under GAAP, any loan modified in a TDR is an impaired loan. Although a loan retains a TDR designation for accounting purposes for life, regulatory reporting requirements allow for a narrow reporting exception. In general, if a TDR borrower complies with the modified loan terms and the loan yields at least a market interest rate when the loan is modified, the loan does not have to be reported as a TDR on the Call Report in calendar years subsequent to the year in which it was restructured. This is only a reporting exception, as the loan is considered TDR for life for accounting purposes (that is, until it is paid in full or otherwise settled, sold, or charged off). Refer to the "Troubled Debt Restructurings" entry of the Call Report Glossary for accounting guidance.

Summary

Just as the credit crisis called for bankers to adapt to a changing environment, improving trends in credit also bring a new set of challenges. It is imperative for bankers to equip themselves with the resources and knowledge required for accounting challenges and complexities. By familiarizing themselves with all available methods of accounting, bankers can be better prepared to ensure compliance, properly document gains and losses, and manage different conditions related to both the bank and the borrower.

In addition to the Call Report Glossary instructions, regulatory examination handbooks, specific ASC guidance, SR letters already mentioned, and their own accountants, banks may find the following resources helpful:

Federal Reserve Supervision and Regulation (SR) Letters:

- SR letter 12-10, "Questions and Answers for Federal Reserve-Regulated Institutions Related to the Management of Other Real Estate Owned (OREO)"

- SR letter 09-7, "Prudent Commercial Real Estate Loan Workouts"

Federal Reserve "Ask the Fed" teleconferences, in which bankers can participate and view archived presentations:

- "Interagency Supervisory Guidance Addressing Certain Issues Related to Troubled Debt Restructurings," November 14, 2013

- "Accounting Hot Topics" (includes discussion of nonaccruals), August 13, 2013

- "More Answers to Your OREO Accounting Questions," December 12, 2012

- "Challenges with Troubled Debt Restructuring," October 19, 2011

For additional information on SR letters and "Ask the Fed" teleconferences, please refer to www.federalreserve.gov/bankinforeg/topics/topics.htm

and www.stlouisfed.org/BSR/askthefed/public-users/login.aspx.

Back to top

-

1

See Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC), "Instructions for Preparation of Consolidated Reports of Condition and Income (FFIEC 031

and 041)," available at www.ffiec.gov/pdf/ffiec_forms/ffiec031_041_200503_i.pdf.

- 2 A below-market rate results in the need to discount the loan to its fair value, effectively reducing the sales price and any gain (or increasing any loss).

-

3

See SR letter 13-17, "Interagency Supervisory Guidance Addressing Certain Issues Related to Troubled Debt Restructurings," available at

www.federalreserve.gov/bankinforeg/srletters/sr1317.htm.