Development and Maintenance of an Effective Loan Policy: Part 1*

by James L. Adams, Supervising Examiner, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia

Loan portfolios typically have the largest impact on the overall risk profile and earnings performance (interest income, fees, provisions, and other factors) of community banks. The average loan portfolio represents approximately 62.5 percent of total consolidated assets for banking organizations with less than $1 billion in total assets and 64.9 percent of total consolidated assets for banking organizations with less than $10 billion in total assets.1

In order to control credit risk, it is imperative that appropriate and effective policies, procedures, and practices are developed and implemented. Loan policies should align with the mission and objectives of the bank, as well as support safe and sound lending activity. Policies and procedures should serve as a framework for all major credit decisions and actions, cover all material aspects of credit risk, and reflect the complexity of the activities in which a bank engages.

Policy Development

While risk is inevitable, banks can mitigate credit risk through the development of and adherence to effective loan policies and procedures. A well-written and descriptive loan policy is the cornerstone of a sound lending function, and a bank’s board of directors is ultimately responsible for framing the loan policies to address the inherent and residual risks (i.e., those risks that remain even after sound internal controls have been implemented) in the lending business lines. Once the policy is formulated, senior management is responsible for its implementation and ongoing monitoring, as well as the maintenance of procedures to ensure they are up to date and relevant to the current risk profile.

Policy Objectives

The loan policy should clearly communicate the strategic goals and objectives of the bank, as well as define the types of loan exposures acceptable to the institution, loan approval authority, loan limits, loan underwriting criteria, and several other guidelines.

It is important to note that a policy differs from procedures in that it sets forth the plan, guiding principles, and framework for decisions. Procedures, on the other hand, establish methods and steps to perform tasks. Banks that offer a wider variety of loan products and/or more complex products should consider developing separate policy and procedure manuals for loan products.

Policy Elements

One place to start when determining which key elements should be incorporated into the loan policy is with the regulatory agencies’ examination manuals and policy statements. This article relies primarily on the Federal Reserve’s Commercial Bank Examination Manual,2 which organizes and formalizes the examination objectives and procedures that communicate supervisory guidance to bank examiners on a wide range of topics.

Although this article does not provide an all-inclusive listing of elements one should find in a loan policy, it does outline and discuss the basic elements that should be included in a general loan policy. Loan policies will differ significantly between banks based on the complexity of the activities in which they are involved; however, a general loan policy should incorporate certain basic lending tenets.

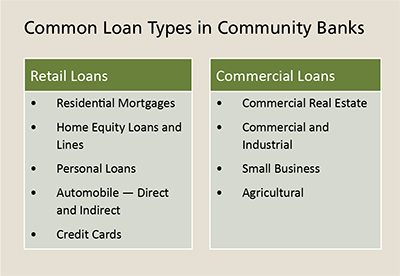

Consistent with the lending strategy, the board should identify not only which types of loans are permissible and impermissible but also the types of loans the bank will and will not underwrite regardless of permissibility. The box to the right outlines some of the more common loan types found in community banks.

Loan Types

Each loan type listed in the box has numerous loan product subcategories. Community banks offer a diverse range of loan products, and this list is by no means all-inclusive. A few of the loan types listed, including home equity3 and commercial and industrial (C&I) lending,4 have been discussed in recently published Community Banking Connections articles. A recent article in the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis’s Central Banker also discusses lending by community banks during the financial crisis.5

In determining permissible lending activity, the board should ask a number of questions such as the following:

- How can we better serve the credit needs of our community?

- Will our primary focus be retail lending, commercial lending, or a mix of the two?

- What types of retail and/or commercial loans will we offer?

- What is our desired mix of loans in comparison with total loans and total assets?

- Do our lending and credit administration staff members have the appropriate skill sets?

Undesirable or impermissible lending activity should also be identified within the loan policy. This will ensure that management and lending staff members do not spend undue time or resources cultivating relationships or pursuing loan types that are not aligned with the bank’s goals or strategy. Undesirable lending activity could include activity that may harm the reputation of the bank or for which the expected return is not commensurate with the level of risk. If the lending staff members do not have the expertise to underwrite, service, or monitor certain loan types, the bank should not undertake such activities. The policy should also state that engaging in the financing of illegal or illicit activities is unacceptable.

Policies and procedures need to be continually evaluated and updated. For example, desirable and undesirable loan types may change as a result of shifting economic conditions, technology, and market demographics, so policies should be reevaluated whenever they are presented to the board for approval.

Loan Participations — Purchases and Sales

The loan policy should adequately address participations, both purchases and sales.6 The most common type of loan participation generally shares profits and losses on an equal basis; therefore, relying solely on the lead banks’ analysis and not conducting independent, thorough analysis is imprudent. Adequate financial analysis and due diligence must be performed prior to entering into any participations.

Participations Purchased. A bank may choose to enter into participations if it is unable to generate sufficient loan demand independently. In this case, partnering with another strong bank operating in a healthier market could help generate additional assets and income. Also, participations may help to diversify risk among locales or lending types. Policies should stress the importance of prudent and independent underwriting, appropriate legal documentation, and ongoing monitoring of loan participations.

Participations Sold. When a bank is unable to advance a loan to a customer for the full amount requested because of lending limits or for other reasons, loan participations may be an appropriate alternative. In such situations, a bank may extend credit to a customer up to the internal or legal lending limit and sell participations to correspondent banks in the amount exceeding the lending limit or in the amount exceeding what the bank wishes to retain. Participation arrangements should be established before the credit is ultimately approved. Participations should be done on a nonrecourse basis, and the originating and purchasing banks should share in the risks and contractual payments on a pro-rata basis. Selling or participating out portions of loans to accommodate the credit needs of customers can promote goodwill and may enable a bank to retain customers who might otherwise seek credit elsewhere.7

If management participates in the underwriting of products similar to loan participation(s), such as syndications8 and/or club deals,9 the loan policy should appropriately cover the basic elements of these activities (limits, underwriting requirements, documentation, and so forth).

For additional information regarding loan participations, bankers should consult the Second Quarter 2013 issue of Community Banking Connections, which featured an article that discussed several ways to strengthen board and senior management oversight of loan participations.10

Loan Portfolio Mix and Limits

The policy should also establish the desired mix of the loan portfolio and limits on individual loan types. Exposure mix and limits should be monitored on an ongoing basis to ensure that they are appropriate and reasonable.

Limits should be determined based on risk tolerances and should be measured in comparison with loans, assets, and tier 1 capital plus the allowance for loan and lease losses (ALLL). Management should continually monitor the dollar and percentage exposures of each portfolio to ensure the bank maintains an appropriate risk profile with sufficient returns. When determining risk tolerances and limits, portfolio stratification is extremely important. Stratification or segmentation of the loan portfolios can be accomplished through numerous variables, depending on the desired granularity. Limits established by general loan type (e.g., commercial real estate (CRE), C&I, and small business) will provide a very broad portfolio overview. Using North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) codes will provide general industry and subindustry categories that should provide greater granularity and insight into the portfolio composition and risk characteristics. Management may also consider stratifying by borrower risk rating, collateral type, loan officer, or other variables.

Concentrations of credit and the legal lending limit are closely linked to portfolio mix and established limits; therefore, these topics are covered within this section.

Concentrations of Credit. Concentrations of credit are defined as exposure to an industry or loan type in excess of 25 percent of tier 1 capital plus the ALLL. Concentrations are not necessarily indicative of performance issues and quite often exist within portfolios. However, risk management practices should be commensurate with the risk profile of the concentrated exposure.

Banks with concentrations in specific types of loans with common characteristics — for example, common industries and/or geographic areas — can be negatively impacted by a catastrophic event within the business line, industry, or geography. Therefore, banks need to have well-established policies and procedures that stress the identification of and the prudent controls over concentrations. Appropriate risk diversification through the establishment of prudent concentration limits may help to minimize the potential negative impact on earnings performance and/or capital should such an event occur.

In 2006, the federal banking regulatory agencies issued guidance on CRE concentrations.11 The guidance addressed the agencies’ observation that CRE concentrations had been rising at many institutions, especially at small-to-medium-sized institutions. While most institutions had sound underwriting practices, the agencies observed that some institutions’ risk management practices and capital levels had not evolved with the level and nature of their CRE concentrations. Therefore, the agencies issued the guidance to remind institutions that strong risk management practices and appropriate levels of capital are important elements of a sound CRE lending program, especially when an institution has a CRE concentration or a CRE lending strategy that could lead to a concentration.

Legal Lending Limit. The loan policy should appropriately address the legal lending limit, which is the aggregate maximum dollar amount that a single bank can lend to a given borrower. Because the legal lending limit is tied to the bank’s capital, management must calculate and monitor the legal lending limit on an ongoing basis.

State-chartered banks must comply with the legal lending limits established by the law of the state in which they are chartered. Some states have adopted parity provisions in their state banking laws that provide state-chartered banks with the option of complying with either the state legal lending limit or the limit established by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency for national banks.12

Geographic Area

Community banks are typically established to serve the local communities in which they operate. The loan policy should identify the geographic area in which an organization will lend and the circumstances under which credit may be extended outside of that area. Familiarity with the geographic area provides insight and supports management’s ability to closely and continually monitor borrower performance.

Lending outside of the local market can help to diversify geographic exposure, as explained in the loan participation section above, but it can also raise concerns about management’s ability to closely monitor projects and remain informed about the local economy. Appropriate policies and procedures covering loan participations and potential concerns with out-of-area lending will help reduce, but not eliminate, some of these risks.

Structure of Lending Function

The structure of the lending department or function varies widely among institutions. Ideally, the lending function should have an appropriate segregation of duties and independence in the roles throughout the department.

Management must strive to maintain sufficient controls and segregation of duties in all lending functions to avoid inappropriate credit decisions and/or weak underwriting processes. The ability to separate the activities of the loan generation function from the credit underwriting and analysis function has numerous benefits. Unfortunately, this is very difficult and often unrealistic at smaller banks, where these activities are usually combined. Smaller banks may struggle with implementing such controls and structure because of their limited staff and financial constraints.

Lending Authority

The loan policy should also clearly define the individuals and loan committees that have the authority to approve loans. Dollar limits should be established for individuals by name or by job title, individuals acting together (dual or multiple individual lending authority), loan committees, and the legal lending limit authority (board or committee thereof). Individual lending authority should be structured by job title and loan product, ensuring that lending decisions are being made by individuals with the appropriate credentials and expertise. However, no bank should delegate unlimited lending authority to one or a limited number of individuals.

Before a bank can establish lending authorities or limits, the board must establish the approval hierarchy or structure. The board is ultimately responsible for the affairs of the organization and must determine to what degree the board is willing to delegate lending authority. The board could determine that it will participate directly, establish a committee of the board, or delegate the authority to a senior management committee. In accordance with the Federal Reserve Board’s Regulation O, the board must be involved in the ultimate credit decision when approving loans to insiders.

Conclusion

Regulators expect community banks to establish and maintain policies that provide an effective framework to measure, monitor, and control credit risk. However, community bankers do not need to start with a blank slate. Information on policy development and maintenance is readily available and easily accessible from a number of sources. The regulatory agencies’ examination manuals and handbooks, along with Federal Reserve Supervision and Regulation letters, provide guidance and timely information on emerging issues and regulatory concerns that should be incorporated into the loan policy. In addition, industry associations and private organizations provide ongoing training and current information on effective policy development. While these resources may be helpful and serve as a solid foundation for a community bank loan policy, the importance of tailoring the policy to the banking organizations’ activities cannot be overstressed.

Although this article addresses both what is permissible and who is responsible in a comprehensive community bank loan policy, it is by no means all-inclusive. The next two articles in this series will discuss additional elements that may be incorporated into the policy, such as underwriting, appraisals, risk ratings, pricing, and documentation; ongoing policy review and maintenance; and overall compliance with the loan policy.

Back to top

- *A loan policy should attempt to specify what is permissible, who is responsible, and how activities will be controlled, reported on, and verified. This article, which is the first of a three-part series that covers key elements of a sound community bank loan policy, discusses the what and the who. The next two articles will review the how, touching on topics such as underwriting, appraisals, risk ratings, pricing, and documentation, along with other related topics, such as loan review and postorigination activities.

- 1 Federal Reserve data as of December 31, 2013.

-

2

See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Commercial Bank Examination Manual (CBEM), section 2040.1, “Loan Portfolio

Management,” available at www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/supmanual/cbem/cbem.pdf.

- 3 See Michael Webb, “Home Equity Lending: A HELOC Hangover Helper,” Community Banking Connections, Second Quarter 2013, available at www.cbcfrs.org/articles/2013/Q2/Home-Equity-Lending-A-HELOC-Hangover-Helper, and “Home Equity Lending: A HELOC Hangover Helper — Part 2,” Community Banking Connections, Fourth Quarter 2013, available at www.cbcfrs.org/articles/2013/Q4/Home-Equity-Lending.

- 4 See Cynthia Course, “Sound Risk Management Practices in Community Bank C&I Lending,” Community Banking Connections, Fourth Quarter 2012, available at www.cbcfrs.org/articles/2012/Q4/Sound-Risk-Management-Practices-in-Community-Bank-CI-Lending.

-

5

See Gary S. Corner and Andrew P. Meyer, “Community Bank Lending During the Financial Crisis,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Central Banker,

Spring 2013, available at www.stlouisfed.org/publications/cb/articles/?id=2342.

- 6 A loan participation is a sharing or selling of ownership interests in a loan between two or more financial institutions. Normally, but not always, a lead bank originates the loan and sells ownership interests to one or more participating banks. The lead bank retains a partial interest in the loan, holds all loan documentation in its name, holds all original documentation, services the loan, and deals directly with the borrower for the benefit of all participants. See CBEM section 2045.1, “Loan Participations, the Agreements and Participants.”

- 7 See CBEM, section 2040.1, “Loan Portfolio Management.”

- 8 A syndication is a loan made by two or more lenders contracting directly with a borrower under the same credit agreement. Each lender has a direct legal relationship with the borrower and receives its own promissory note(s) from the borrower. Typically, one or more lenders will also take on the separate role of agent for the credit facility and assume responsibility for administering the loans on behalf of all lenders. A syndicated loan differs from a loan participation in that the lenders in a syndication participate jointly in the origination and the lending process.

- 9 A club deal is the smallest type of syndicated loan, usually used for loans between $25 million and $150 million. Unlike the other loan types, the club deal is an equal denomination loan in which all parties lend the same amount; the arranger puts in the same amount as all other lenders, and all parties equally share the loan fee.

- 10 See Michael Poprik, “Loan Participations: Lessons Learned During a Period of Economic Malaise,” Community Banking Connections, Second Quarter 2013, available at www.cbcfrs.org/articles/2013/Q2/Loan-Participations.

-

11

See Supervision and Regulation letter 07-1, “Interagency Guidance on Concentrations in Commercial Real Estate,” and its attachment, available at www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/srletters/2007/SR0701.htm.

-

12

See 12 CFR Part 32, available at http://ow.ly/COXUD.