Recruiting and Retaining Community Bank Directors

by Cynthia L. Course, CPA, Director, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

As community banks move beyond the Great Recession and explore new opportunities for growth and profitability, their outside directors will play an increasingly important role in guiding the banks through both familiar and uncharted territories. Though it may not be as easy to recruit and retain new external community bank directors today as it has been in the past, the challenges are not insurmountable.

This article is not intended to establish or describe supervisory expectations for boards of directors. Rather, it suggests some ways that community banks can think about recruiting and retaining qualified, effective directors and potentially evaluating the effectiveness of the board through self-assessments. Many of the suggestions for ways to recruit and retain qualified directors come from a panel survey of community bankers in the western United States.

Is There an “Ideal” Director Profile?

Given the pace and scope of change in the banking environment, the board of directors collectively and each member individually play a critical role in the overall success of a community bank. This does not mean that each board candidate has to be an expert in banking to be considered for board membership.1 To the contrary, the diversity of experiences, education, views, and opinions can make the strength of a community bank board greater than the sum of its parts.

Given the importance of bank directors in overseeing the successful operation of the bank, is there an “ideal” director profile? In a word — no. As noted previously, a community bank’s board of directors can be strengthened by diversity.

The Federal Reserve recently issued supervisory guidance that discusses certain personal or business experience characteristics that have proven problematic when reviewing applications for directors at de novo and troubled institutions.2 In short, individuals whose backgrounds raise questions regarding their integrity, financial responsibility, or competence, or otherwise raise doubt about their ability to fulfill the responsibilities of a bank director, have been viewed unfavorably.

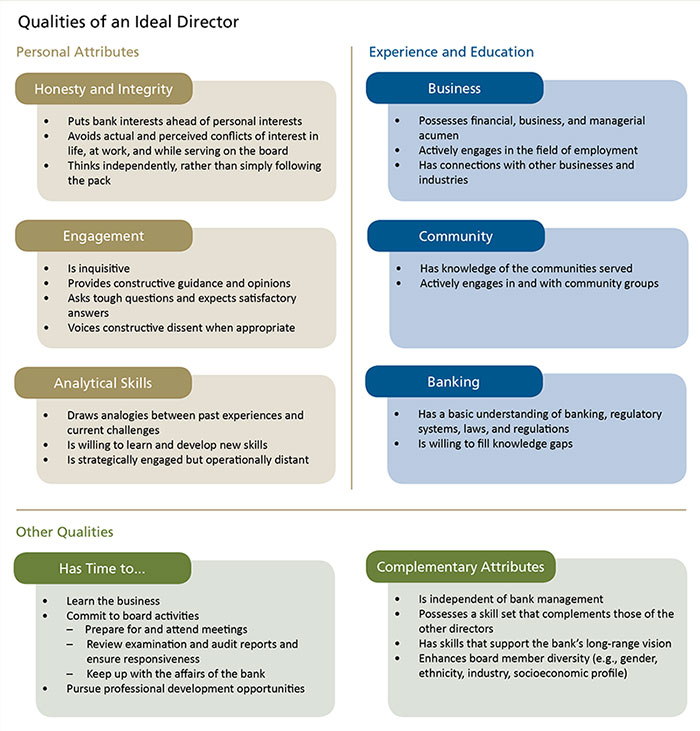

However, for the purposes of this article, it may be more informative to consider the combination of characteristics that could indicate the likelihood that a director will be a good fit for the bank. Most likely, this combination will be a mix of personal attributes, experience and education, and a willingness and ability to dedicate the necessary time to this important role.

The box below illustrates some of the personal attributes, experience, education, and other qualities that are generally found in capable community bank directors.

While there will likely be quite a bit of similarity in the attributes of a capable director across different community banks, the fit of each individual director should be considered within the context of the institution’s strategic direction and culture as well as the attributes, experience, and education of the directors already on or being considered for the board.

Recruiting Community Bank Directors

Given an understanding of the desired characteristics of a director, how can a community bank recruit capable directors?

To ensure the best fit between a director candidate and the bank, the board’s nominating committee or similar subset of the board should assess the skills and demographic profile of its current directors, compare the skills and profiles with the bank’s strategic direction and risk profile, and identify any collective gaps. This exercise will increase the likelihood that the board will find an individual with the skills, abilities, talent, and commitment to make a difference. Importantly, it will become the “bottom line” in the discussion with the candidate about how he or she will be able to make a direct impact on the bank’s success.

Admittedly, recruiting new bank directors may have been easier to do in the past than it is today. Historically, many business and community leaders considered it an honor to be asked to serve on their community bank’s board of directors. These candidates viewed membership on the board as evidence of their business expertise and prominence in the community, and they appreciated the shareholders’ vote of confidence in their skills. While serving on a board of directors is indeed an honor, many may now also weigh the benefits against the potential burden or legal liability.

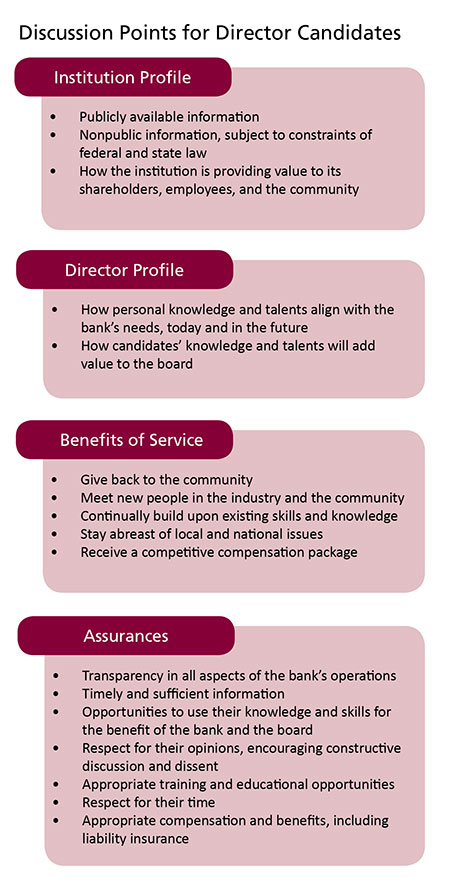

Today, recruiting new directors often requires the members of the nominating committee to “sell” potential director candidates on board membership. This includes having frank discussions with the candidate about the institution3 and how he or she can contribute to the bank’s future. This also includes discussing the benefits of serving as a bank director and giving reasonable assurances to the candidate about the board’s expectations of and commitment to each member.

Community banker nominating committees can consider the points that are detailed in the box below when preparing discussion topics to use when approaching director candidates.

When done effectively, the process of recruiting qualified directors will be very similar to recruiting qualified executives, but with the shareholders having the final say on the nominee.

Retaining Strong Bank Directors

Once the bank’s shareholders have elected a director to the board, the board’s focus should shift from recruiting to engagement and retention. To be most effective, efforts to engage and retain capable directors should begin the moment they are appointed and should continue throughout their tenure.

Orientation. Effective community banks will develop an orientation program that is tailored to the size and complexity of the bank and the experience and knowledge of each new director. Elements of a comprehensive orientation program could include:

- Meetings with the heads of each business line to gain an understanding of the challenges and opportunities in each area

- Meetings with other board members

- Introductions to key external parties, such as bank counsel, bank auditors, and bank examiners

- Access to materials not made available during the

recruitment process, such as bank examinations and audit reports -

Demonstrations of access to virtual private networks

or other information-sharing tools used by the board

of directors - Access to director training materials commensurate with the director’s experience, such as the Federal Reserve System’s Bank Director’s Desktop 4

Culture and Atmosphere. A professional and inclusive culture and atmosphere within the board and between the board members and management should enhance director retention. Directors are more likely to remain on the board when:

- Management is transparent about all aspects of the bank’s operations.

- The board receives timely and sufficient information to make sound decisions.

- The board is empowered to make decisions.

- The board members are treated with respect.

- Management is respectful of the board’s time.

- Management sincerely seeks the directors’ input and shows appreciation for the board’s contributions.

- There is a clear linkage between the board’s activities and the organization’s success.

Education and Training. Ongoing education and training are as important for community bank directors as they are for the bank’s staff and management. However, there is a delicate balance between maintaining respect for the directors’ time commitment and ensuring that they have the knowledge necessary to make informed decisions. While directors are expected to bring to the boardroom the views and perspectives gained from their personal and professional experiences, they must also be able to put those views in the context of the bank and the environment in which it operates.

Each director should possess knowledge of the bank and the banking industry that is appropriate for his or her tenure. In addition, each board member should be expected to complete continuing education and training to build upon and maintain the skills necessary to be an effective community bank director. Board members may find that choosing from a variety of educational opportunities, such as the following, helps them balance time constraints against information needs:

- Targeted training or education sessions as a part of board meetings

- Annual director retreats that focus on training as well as strategic planning and bank operations

- Subscriptions to print or electronic periodicals and newsletters that discuss current and emerging community bank issues

- Attendance at banker association, trade group, or regulatory conferences and seminars, with formal debriefings to the other directors at board meetings

Recognition. Recognizing director contributions, whether through words and actions or through monetary compensation, is also a significant element in director retention. Recognition and compensation can be tailored to each director’s contributions; however, they generally will not be sufficient to retain capable directors without an atmosphere and culture that is conducive to effective board operations and sufficient education and training to ensure that each director is well informed.

Evaluating Board Performance

To remain strong and independent, community bank boards of directors may find value in periodically evaluating their effectiveness and identifying opportunities for improvement and growth.

Community bank boards may find that self-assessments are effective at highlighting emerging governance issues.5 For example, a board self-assessment at the highest level could ask focused questions about the board’s primary responsibilities. Subsequent questions could drill down into the board members’ perceptions around the bank’s mission and purpose, the effectiveness of strategic planning, the sufficiency of succession planning, the appropriateness of the board’s monitoring and control activities, and the involvement of the bank in its community. Self-assessments can also provide valuable insight into the functioning of the board through questions that address ethics, the interpersonal relationships among board members, the selection and training of directors, the effectiveness of dialogue at board meetings, the engagement and contribution of individual directors, and the organization of the board and its committees.

Completing the circle, the periodic use of self-assessments may also help a community bank’s nominating committee recruit new directors. Candidates likely will be more interested in joining a company that seeks out and acts upon holistic director feedback than a company in which director feedback is sought only on very narrow and specific decisions.

Concluding Thoughts

Banks play an important role in the economic lives of their communities, and community bank directors have a great opportunity to influence and help shape their local economies. For a community bank, recruiting and retaining qualified and effective directors is as important as recruiting and training an effective management team. In the words of a former board chairman and member, “At the end of the day there’s nothing like a strong board that operates independently, asks good questions, and does its homework.”6

Back to top

- 1 Although board candidates are not required to have expertise in banking when they are appointed to the board, they are expected to quickly become familiar with the basics of banking in order to provide effective oversight of management and to make informed decisions. In addition, a bank that is a public company subject to Securities and Exchange Commission oversight is required to have an audit committee financial expert on its board of directors and audit committee.

-

2

See Supervision and Regulation (SR) letter 14-2/Consumer Affairs (CA) letter 14-1, “Enhancing Transparency in the Federal Reserve’s Applications Process,”

available at www.federalreserve.gov/bankinforeg/srletters/sr1402.htm.

- 3 Federal and/or state laws may limit the nature of information that can be shared with director candidates. For example, banks are prohibited by law from disclosing their bank and holding company supervisory ratings and other nonpublic supervisory information to nonrelated third parties without written permission from the appropriate federal banking agency. See “Confidential Supervisory Information Disclosure Rules” in the First Quarter 2013 issue of Community Banking Connections, available at www.cbcfrs.org/articles/2013/Q1/Confidential-Supervisory-Information-Disclosure-Rules.

-

4

See www.bankdirectorsdesktop.org/.

-

5

Recommending a specific self-assessment process is beyond the scope of this article, and the Federal Reserve does not endorse any specific self-assessment

tools or templates. However, a variety of resources for community bank boards of directors interested in developing self-assessments is available through

trade groups such as the Bank Director website and magazine at www.bankdirector.com/.

-

6

Comment by Lew Platt, former chairman, board member, and chief executive of Hewlett-Packard, while serving as a Boeing board member, as referenced in Knowledge@Wharton, “Re-Examining the Role of the Chairman of the Board,” December 18, 2002, available at http://ow.ly/Cghop.