Banks Are Becoming More Efficient — Is That Good or Bad?

by Wallace Young, Director, Risk Coordination Unit, and Alex Lightfoot, Senior Risk Specialist, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

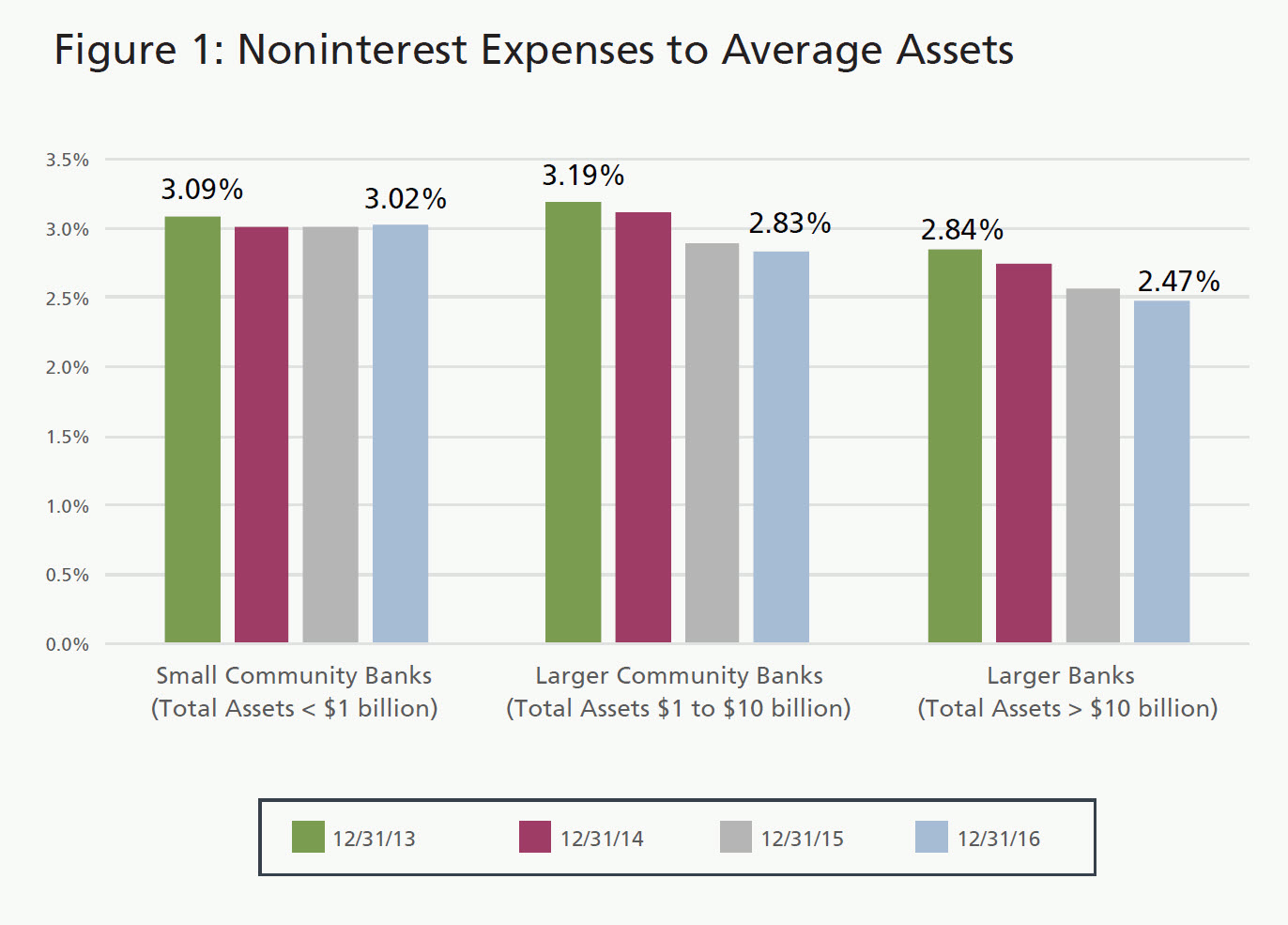

Although the extended low interest rate environment has made it challenging for many banks to improve profitability, net income in the banking industry is rising, largely because of efficiency gains. At many banks across the nation, overhead expenses (otherwise known as noninterest expenses) are increasing but at a much slower pace than total assets. For example, average noninterest expenses as a percentage of average assets at small community banks across the nation (those with total assets below $1 billion) have slowly declined from 3.09 percent at December 31, 2013, to 3.02 percent at December 31, 2016, a drop of 7 basis points (Figure 1). For larger banks, the decline is much more noticeable; since year-end 2013, noninterest expenses as a percentage of average assets have declined 36 basis points at larger community banks (with total assets between $1 billion and $10 billion) and 37 basis points at banks with assets above $10 billion.1

These declines may not seem that significant, but over this same period, return on average assets (ROAA) at banks across the nation has actually decreased slightly by 5 basis points, as net interest margins (NIMs), net interest income as a percentage of average assets, have hovered in a very tight range for most institutions. In this low interest rate environment, banks face challenges to further improve core earnings; therefore, even a modest reduction in overhead expenses will likely have a material impact on a bank’s profitability.

The fact that the industry is operating more efficiently is a positive development. However, it is somewhat surprising that some banks are able to boost efficiency at a time when operating and information security costs are reportedly rising, which raises the following question: Can a bank be too efficient? Some minimal level of overhead is necessary to ensure that the institution is devoting sufficient resources to all the various operations across the organization, including its administrative, human resources, compliance, and audit functions.

With this in mind, this article explores the improving efficiency trend to uncover some ways that banks are becoming more efficient and highlights a number of issues that bank management teams should consider as they balance a desire to operate more efficiently against the need to devote appropriate resources to all functions in the organization.

Why (and How) Are Banks Becoming More Efficient?

The motivation to improve efficiency is not unique to the banking industry. Most companies are regularly looking for ways to operate more efficiently, as more efficient businesses are often more profitable and better positioned to generate higher returns for their owners. More often than not, technological advancements enable businesses to operate more efficiently. Certainly, the banking industry has seen numerous technological advancements over the past several decades, such as the advent of the computer itself, the invention of the automated teller machine (ATM), the evolution in electronic payments, and the proliferation of online banking. Many of these technological advancements not only make banking more convenient for the consumer, but they also allow banks to build a much larger organization with relatively fewer staff, branches, and support offices. For example, over the past several years, a big shift has been seen in how customers interact with their banks. Although many bank customers may not want to see their local branches close, most are less inclined to visit a bank branch to conduct banking activities. As a result, banks need fewer branches and, correspondingly, fewer employees and physical assets such as copy machines, file cabinets, and office furniture. In fact, the number of bank branches in the U.S. has declined by 6 percent since 2009, and there is speculation that banks can do even more trimming as customers continue to embrace online and mobile banking services.2

In the meantime, as credit quality across the industry continues to improve, there are fewer problem assets that need to be worked out. This has led to a natural decline in operating expenses (e.g., legal expenses), as fewer problem assets mean that there is less need to engage legal counsel to assist with document review and various legal filings. Also, over the past several years, there have been advancements in risk management techniques that have helped management teams manage even larger and more complex organizations. For example, advancements in data analytics allow bank management teams to develop and analyze increasing amounts of data, which result in the need for fewer staff or management to oversee the staff.

So, there are several reasons to explain why banks are becoming more efficient; however, it is also possible that bank management teams are more inclined to seek out improvements in efficiency as a way to boost net income during this extended period of very low interest rates. Despite robust loan growth over the past several years, bank management teams have found it difficult to improve NIMs and may face increased pressure to reduce operating expenses.

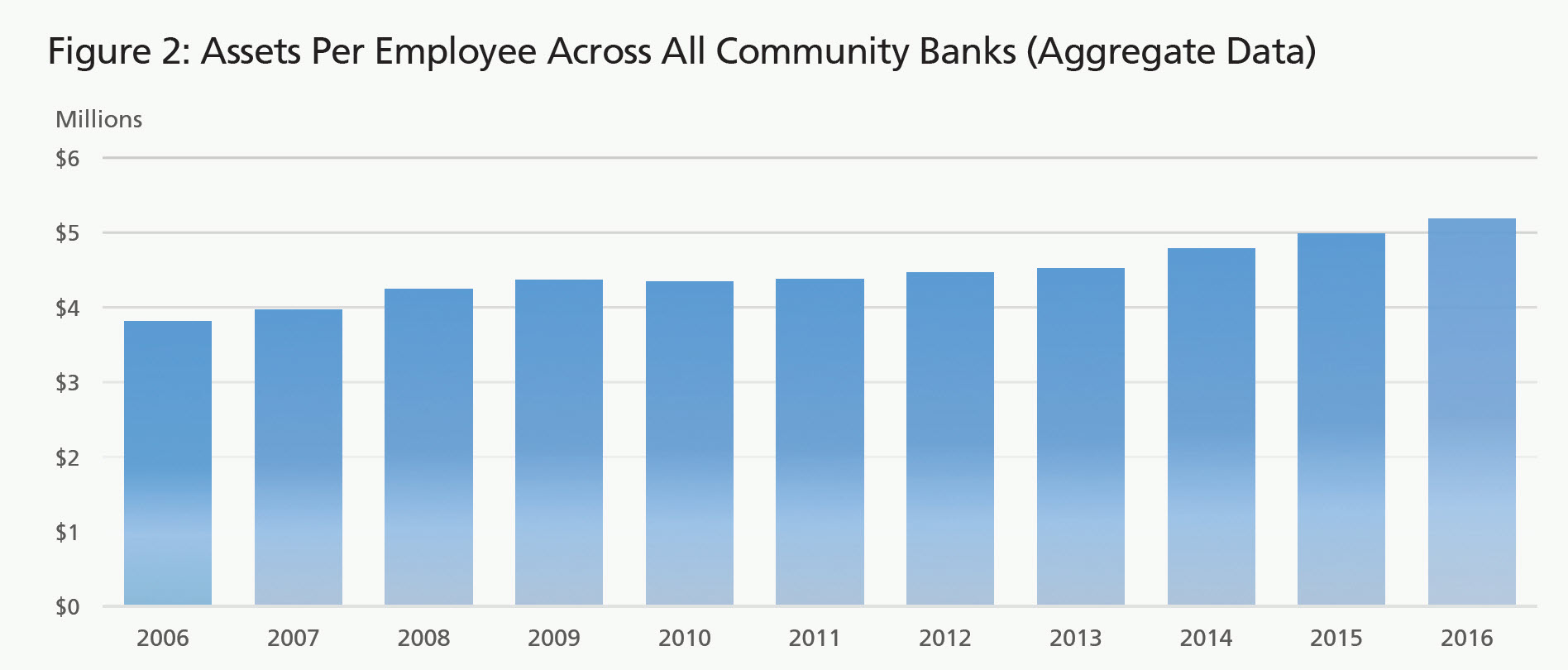

Whatever the motivation, many institutions are seeking outright cuts to employee count, while others are tightly controlling personnel and other operating expenses to lag asset growth. One measure that highlights this trend is the growth in overhead expenses against asset growth. This can be highlighted in the continuously rising number of assets per employee (Figure 2). Closely managing employee count appears to be a common (and even obvious) method for improving efficiency, but asking staff to do more with less puts additional pressure on bank staff. Meanwhile, bank management teams become more reliant on relatively fewer staff to perform day-to-day activities and to ensure proper internal controls are followed.

To What Extent Is Improving Efficiency Leading to Stronger Net Income?

After several years of consistent improvement, net income (as measured by pretax ROAA) at all community banks has slowed to varying degrees. At small community banks, pretax ROAA has increased from 1.09 percent at year-end 2013 to 1.28 percent at year-end 2016. However, at larger community banks, ROAA has actually declined nominally, from 1.54 percent to 1.51 percent over this same period. Meanwhile, over this period, NIMs actually declined for both groups of community banks, from 3.69 percent to 3.66 percent at small community banks and from 4.00 percent to 3.61 percent at larger community banks.3

Therefore, the improvement in pretax ROAA over this period was not driven by improvement in core earnings. Instead, the stronger earnings performance at these banks was due to lower credit-related costs (provisions for loan and lease losses) and/or operating expenses (noninterest expenses). Provisions for loan and lease losses declined modestly at small community banks, from 0.18 percent of average assets at year-end 2013 to 0.13 percent at year-end 2016. Provisions for loan and lease losses increased slightly at banks with total assets of $1 billion to $10 billion, from 0.21 percent at year-end 2013 to 0.26 percent at year-end 2016. However, noninterest expenses declined more significantly over this period, particularly for larger community banks. As previously mentioned, at small community banks, the decline in noninterest expenses over this period equaled 7 basis points, but it was much more meaningful at the larger community banks (36 basis points), indicating that net income, particularly at larger banks, was driven primarily by a decrease in operating expenses.4

What Concerns Arise When Banks Become More Efficient?

While there are several benefits to banks becoming more efficient, a strategic decision to make an organization more efficient, if not managed appropriately, could hurt the financial health of the institution in the long run. If bank management chooses to improve efficiency by cutting staff or limiting the growth in employee count as the balance sheet grows, it may quickly encounter internal control challenges or other operational breakdowns. For instance, if resources in the bank’s internal loan review department do not increase in line with loan growth, internal loan review staff could quickly become overwhelmed, and a previously effective operation could become ineffective.

One common metric that is used to measure and monitor an institution’s overall efficiency is the efficiency ratio (total noninterest expenses divided by the sum of noninterest and net interest income). The lower this ratio, the more efficient the organization is when compared with other institutions. Concerns arise when a low efficiency ratio is driven by the numerator rather than the denominator. Put differently, a low efficiency ratio that is the result of declining and/or lower overhead expense (the numerator) will be viewed with more concern by regulatory authorities than a low ratio that is the result of relatively larger levels of noninterest or net interest income (the denominator).

Over the past several years, the overall efficiency ratio for the banking industry actually has not moved much. However, there does appear to be a widening range of ratios, and there is a pronounced decline in efficiency ratios for banks in certain markets. For example, for banks in the Federal Reserve’s Twelfth District, the aggregate efficiency ratio of 56 percent is nearly 5.5 percentage points lower than the aggregate efficiency ratio for all banks nationwide. Moreover, there are several institutions in the Twelfth District that now have extremely low efficiency ratios, with some still moving downward and approaching the 40 percent level.5 Further, many of these ratios are indeed driven by lower overhead expenses, which could draw some regulatory attention, particularly if these same institutions also have internal audit or other internal control deficiencies. In fact, in the Twelfth District, there has been a rise in the number of banks that have internal audit program deficiencies.

What Could Go Wrong?

One institution that was experiencing significant asset growth soon found that its Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) compliance team was overworked and too thinly staffed to ensure its BSA compliance program was working appropriately. The bank, which previously had a satisfactory BSA compliance program, learned that it was no longer in full compliance with the BSA. The management team was slow to recognize that as the institution quickly grew so too did its BSA risk profile. This unanticipated development required the institution’s management team to quickly shift gears, slow down its expansionary plans, and focus on hiring additional BSA staff to address the backlog of work and implement the program enhancements necessary to ensure that the program was appropriately scaled to handle the increased risk profile.

What Should Bank Management Teams Keep in Mind?

In the current low interest rate environment, it is especially important that bank management teams pay particular attention to operating expenses and promote efficient operations. However, short-term profits should not come at the expense of long-term viability. Bank management teams also need to ensure that the institution is appropriately staffed and that sufficient resources are in place to effectively manage all areas of the institution’s operations. As an institution grows in size and complexity, it will naturally require more resources to manage increasing risks. The difficult part of the process is determining just how many additional resources are necessary. With that in mind, as bank management teams focus attention on increasing profits, they should consider the following:

- Incorporate staffing and resource needs into the strategic planning process. Boards of directors and bank management teams at most banks already develop an annual strategic plan that is used to guide their organizations’ operations. The strategic planning process used by a bank is going to vary widely given the bank’s size, complexity, and type of operations, but often these plans are developed by simply incorporating new growth targets for the bank’s various lines of business and areas of operations. On the expense side, very high-level targets will often be established (e.g., “personnel expense will grow 5 percent over the next 12 months” or “personnel expense will decline 5 percent”). While there may be some good rationale for determining these growth rates, it is still a top-down approach, and it may not be clear whether that specific level of personnel expense is appropriate for the bank’s business model and type of operations.

- Incorporate efficiency metrics into peer analysis. Similarly, most bank management teams already conduct some form of peer analysis to see how their bank’s performance compares with that of a designated peer group. This peer analysis should incorporate efficiency metrics. Peer analysis is useful; it can help management teams identify areas in which the bank is performing not as well as or much better than its peers. Efficiency metrics such as the efficiency ratio, overhead expense to average assets, and average personnel expense per employee (all of which are available in the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council Uniform Bank Performance Report6) can show how the bank is financing its operations relative to its peers. Operating expenses that are substantially lower than those of its peers (factoring in variances in business models) should be viewed as a red flag and investigated by the management team.

- Monitor root causes of operational breakdowns. From time to time, even the best-run organization will have some breakdown in its operations, internal controls, or compliance programs, and even the best organization will receive an occasional adverse audit finding. These things happen despite the best intentions and sound risk management programs. As gaps are identified, bank management teams should focus their attention on root causes. When the root causes point to a theme of inadequate staffing, resources, or expertise in different areas of bank operations, this could be a signal that the bank is not devoting sufficient resources to its various operational functions.

Bringing It Home

To close, it is important to reinforce the point that efficiency is good. Any organization will be more successful if it closely manages its growth and expenses. On that note, management teams should not be so focused on profitability metrics that they forget about the need to maintain appropriate internal controls, audit functions, and compliance programs, especially as the institution grows in size, complexity, and/or risk profile. At times, it may be totally appropriate to make some tough decisions and sacrifice current income for long-term profitability to staff-up an important operational function in order to better position the institution to manage its risk for the long term.

Back to top- 1 The data were obtained from the aggregate reports developed by the Surveillance staff at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System using the Consolidated Reports of Condition and Income (Call Report).

- 2 Dan Freed, “Bank Customers Don’t Want Their Local Branches to Close,” Money Magazine, August 22, 2016.

- 3 Data obtained from the Call Report.

- 4 Data obtained from the Call Report.

- 5 Data obtained from the Call Report.

- 6 See the Uniform Bank Performance Report, available at www.ffiec.gov/UBPR.htm.