Less Risky Business: An Overview of a New Cybersecurity Assessment Tool

by Brian Bettle, Senior Examiner, Supervision and Regulation, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

Over the years, financial institutions have increased their level of maturity with respect to business continuity and disaster recovery so that they may better manage environmental events, such as tornadoes, earthquakes, and hurricanes, that could affect their organizations. Managing through environmental events has become part of the normal course of business for many financial institutions, especially those in regions prone to these events. As a result, these financial institutions have very robust business continuity and disaster recovery plans. The plans are tested annually and are often activated when severe weather events are anticipated. Financial institutions operating in this type of environment have learned to adapt quickly and resume operations with minimal impact on customers after the weather-related event is over.

Since cybersecurity is becoming one of the greatest risks that can affect financial institutions today, these organizations need to react similarly to this growing threat by enhancing their cybersecurity maturity levels. Since the 2012 distributed denial-of-service attacks,1 financial institutions have placed greater emphasis on improving security and combating potential incidents. Financial institutions have increased their information technology (IT) security budgets and invested in systems and personnel to address these risks. Despite these efforts, financial institutions are unsure whether their actions are sufficient and whether their preparations and ongoing security programs adequately address the risks.

Members of the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC)2 have also experienced challenges in assessing whether financial institutions’ actions are appropriate and sufficient. Therefore, the organization developed a cybersecurity assessment tool (CAT) that is designed to help financial institutions determine their inherent level of cybersecurity risk and then assess the appropriateness of their cybersecurity control environments given their identified risks. This tool is based on the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Cybersecurity Framework and existing regulatory guidance. The CAT is not a silver bullet to address all cybersecurity concerns. However, the tool should help an institution identify control gaps in its operating environment based on its inherent risk profiles. The supervisory expectation is that an institution will assess its cybersecurity risk; the CAT provides one option to perform this assessment.

Implementation

On July 2, 2015, the Board of Governors issued Supervision and Regulation (SR) letter 15-9, “FFIEC Cybersecurity Assessment Tool for Chief Executive Officers and Boards of Directors.”3 The letter includes information on the CAT. The Federal Reserve plans to use these self-assessments in the review of cybersecurity preparedness during the IT and safety-and-soundness examinations and inspections. As part of the examination process, examiners will assess a firm’s self-assessment of cybersecurity risk. The use of the CAT remains voluntary; however, firms are expected to perform a cybersecurity assessment using either the CAT or an industry-accepted practice, such as the NIST Cybersecurity Framework or ISO 27001.

Establishing an Inherent Risk Profile

The first portion of the CAT process focuses on an institution’s current inherent risk environment. The tool helps determine the level of cybersecurity risk based on a firm’s activities, services, and products. The CAT measures five inherent risk categories.

- Technologies and Connection Type. The assessment begins with measuring the inherent risk of technologies and connections. Certain connections may pose additional cyber-related risks. The risk profile may be adjusted depending on the number of Internet service providers and third-party connections used and whether they are in-house or outsourced. The volume of unsecured connections and the use of end-of-life systems, cloud services, and personal devices can also increase the risk at a firm.

- Delivery Channels. Numerous delivery channels for products and services may pose a higher level of inherent risk. The increase in the risk level depends on the nature of the specific product or service offered and is elevated as the variety and number of delivery channels increase.

- Online Mobile Products and Technology Services. The use of online and mobile delivery channels can also influence the inherent risk levels. The greater the number of online and mobile delivery channels and the use of smart automated teller machines (ATMs) — those with touch screens that provide onscreen directions through the entire transaction — the greater the risks. Expanding the number of delivery channels also presents cyber-related risks due to the additional paths that an attacker can use to exploit a target. A financial institution’s mobile or online services may also heighten risk, particularly if a funds transfer component is available.

- Organizational Characteristics. This category can also raise the inherent cybersecurity risk at a firm. In some instances, data breaches occurred after a merger because of a lack of control over the newly consolidated environment. In the postmerger environment, compiling a comprehensive inventory of hardware can be challenging. An overlooked server can go without security updates for a significant amount of time, which opens the door to a data breach. Also, in a postmerger environment, changes in staffing or the use of contractors can lead to excessive user-access privileges being granted and then overlooked. Lastly, organizational changes can also affect morale, which may increase the potential of an insider security threat.

- External Threats. The last inherent risk factor comes from external threats. A large multinational financial institution will have a higher risk profile than a small community bank in a rural setting. Both firms will always face the potential for a cyberattack. However, a small community bank may be unknown outside of its market area and face fewer threats. Although community banks may not be well known internationally, they remain at risk because they are often perceived to have fewer cybersecurity controls in place.

Considering Cybersecurity Maturity

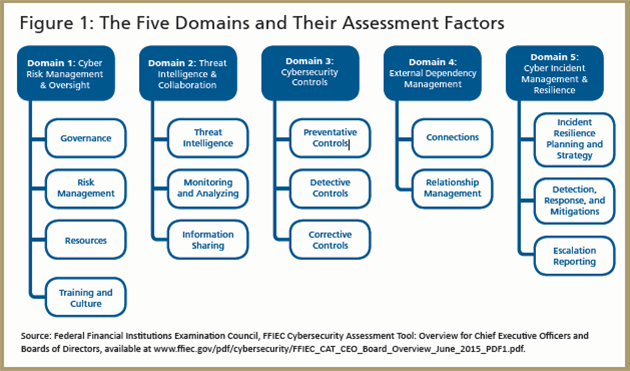

The second portion of the CAT focuses on assessing the cybersecurity maturity of a firm’s control environment. This maturity assessment is based on the following five domains:

- Cyber Risk Management and Oversight — the governance infrastructure that a firm has in place to oversee cyber-related risk

- Threat Intelligence and Collaboration — the capability to monitor, acquire, analyze, and track the potential cyberthreat landscape and how it might affect the firm

- Cybersecurity Controls — the measures put in place to deter and prevent a cyberattack

- External Dependency Management — how well a firm manages its vendors, including an assessment of the robustness of its vendor management program

- Cyber Incident Management and Resilience — the steps management takes to identify, prioritize, respond to, and mitigate cyberthreats and vulnerabilities when they occur

Figure 1 details the five domains and the assessment factors that inform these domains. For each assessment factor, the table below provides a set of declarative statements that describe activities that inform the level of maturity for each domain.

Source: Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, FFIEC User’s Guide, available at www.ffiec.gov/pdf/cybersecurity/FFIEC_CAT_User_Guide_June_2015_PDF2_a.pdf.

Using the CAT

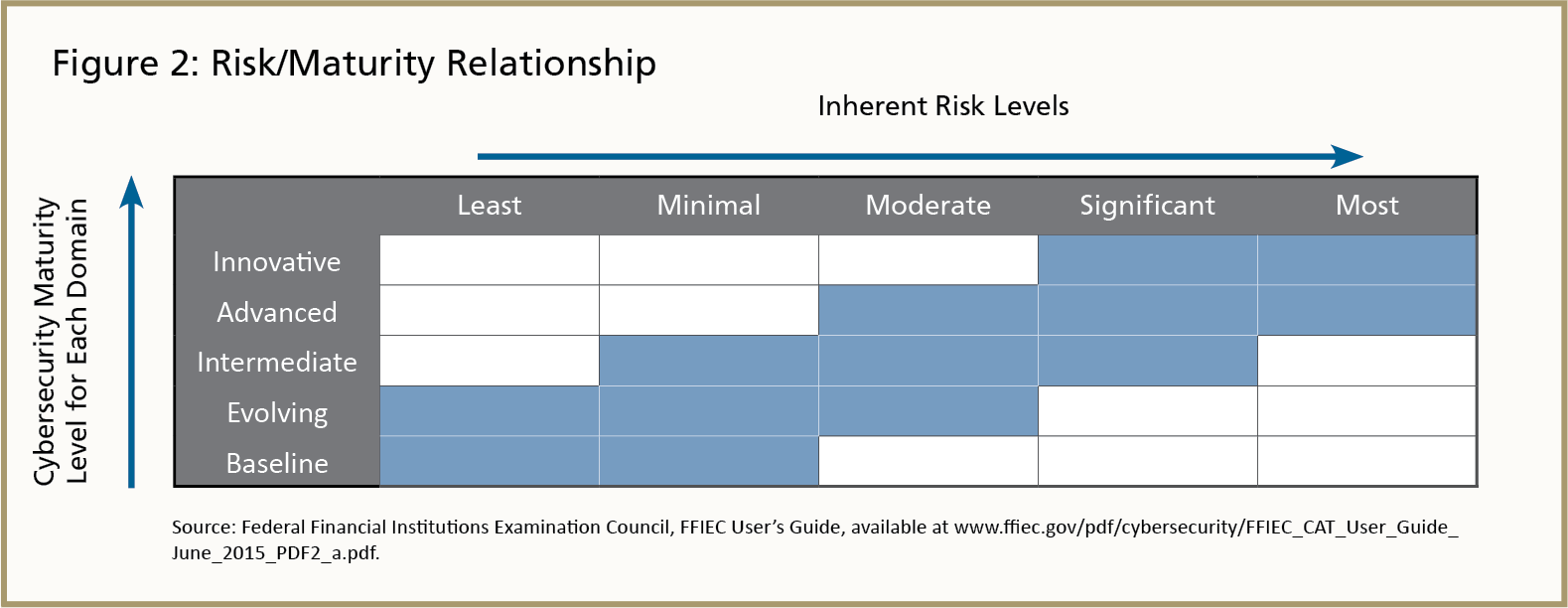

The CAT provides an institution’s management and board of directors with a repeatable and measurable process to determine whether the institution is applying sufficient resources and has the appropriate controls to manage cybersecurity risk. The CAT can help inform management and the board about the institution’s level of inherent cyber-related risk. The board may then consider this information and, given its risk appetite, determine the appropriate level of cybersecurity maturity needed to manage the institution’s particular risk environment. Not all financial institutions are expected to be at an innovative level of maturity. In fact, very few need to strive for this level. Figure 2 helps to define the appropriate levels of maturity based on the inherent cybersecurity risk identified.

After the board determines the desired maturity level, management can then measure the current processes against this level, identify any gaps, and take action to move the institution’s control environment toward the desired outcome.

Concluding Thoughts

An institution may wish to compare its preparation for a cyberevent with the preparation that financial institutions regularly undertake in advance of a severe weather event. For example, the Federal Reserve examines many financial institutions and technology service providers in the southeastern United States for potential risks arising from a hurricane. As a result, these financial institutions have very robust business continuity and disaster recovery plans. Plans are tested annually and are often activated during severe weather events. Given this operating environment, these financial institutions have learned to adapt quickly and resume operations with minimal impact on customers in the aftermath of a weather event. Therefore, financial institutions across the United States should seek to maintain a cybersecurity maturity consistent with their inherent risk profile. Firms should assume that it is only a matter of time before they experience a cyberevent. In the ideal state of maturity, when a cyberevent happens, an institution will be prepared to react quickly, minimize impact, and resume operations as soon as possible. The CAT is a good first step toward moving the financial industry to this state of maturity.

In the future, the FFIEC will update the tool and the IT Examination Handbook based on the cybersecurity threat landscape. Additional information on the CAT and improving cybersecurity risk management is available.4

Back to top- 1 In the fall of 2012, an unprecedented amount of traffic was directed at the websites of several major banks, causing interruptions, slowdowns, or the suspension of services.

- 2 FFIEC membership includes the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the National Credit Union Administration, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and the State Liaison Committee.

- 3 See SR letter 15-9, “FFIEC Cybersecurity Assessment Tool for Chief Executive Officers and Boards of Directors,” available at www.federalreserve.gov/bankinforeg/srletters/sr1509.htm.

- 4 See www.ffiec.gov/cyberassessmenttool.htm.