What Community Bankers Should Know About Virtual Currencies

by Wallace Young, Director, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

Virtual currencies are growing in popularity. While the collective value of virtual currencies is still a fraction of the total U.S. dollars in circulation, the use of virtual currencies as a payment mechanism or transfer of value is gaining momentum. Additionally, the number of entities (issuers, exchangers, and intermediaries, to name just a few) that engage in virtual currency transactions is increasing, and these entities often need access to traditional banking services. Providing banking services to these entities presents some unique risks and challenges. This article identifies some of the more significant risks that community bank management teams should consider before engaging in this banking activity.

Bitcoin Leads the Way

Launched in 2009, Bitcoin is currently the largest and most popular virtual currency. However, many other virtual currencies have emerged over the past several years, such as Litecoin, Dogecoin, and Peercoin.1 Meanwhile, even more virtual currencies are being developed; one of these is Dash (formerly Darkcoin), which offers even more anonymity and privacy than that provided by Bitcoin. Another new and specialized virtual currency is DopeCoin, which was developed for those who wish to purchase marijuana, either legally or illegally.

Launched in 2009, Bitcoin is currently the largest and most popular virtual currency. However, many other virtual currencies have emerged over the past several years, such as Litecoin, Dogecoin, and Peercoin.1 Meanwhile, even more virtual currencies are being developed; one of these is Dash (formerly Darkcoin), which offers even more anonymity and privacy than that provided by Bitcoin. Another new and specialized virtual currency is DopeCoin, which was developed for those who wish to purchase marijuana, either legally or illegally.

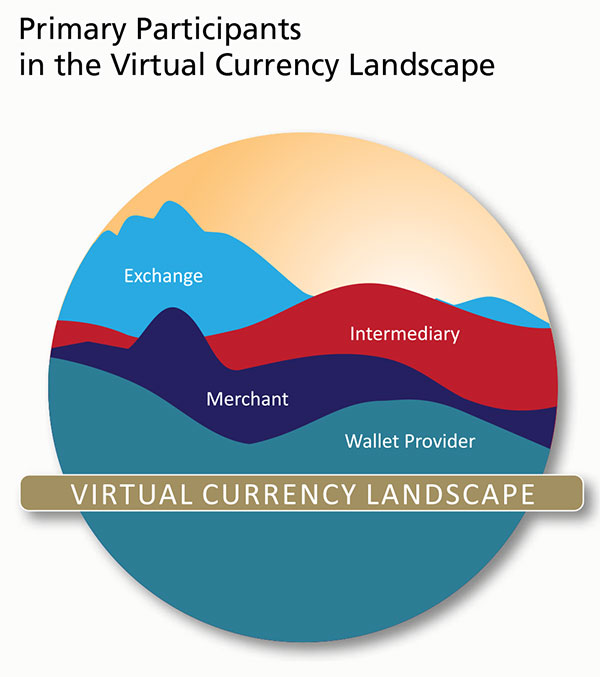

The virtual currency landscape includes many participants, from the merchant that accepts the virtual currency, to the intermediary that exchanges the virtual currency on behalf of the merchant, to the exchange that actually converts the virtual currency to real currency, to the electronic wallet provider that holds the virtual currency on behalf of its owner. Accordingly, opportunities abound for community banks to provide services to entities engaged in virtual currency activities. Eventually, it is also possible that community banks may find themselves holding virtual currency on their own balance sheets.

The Virtual Currency Landscape

Virtual currencies such as Bitcoin are digital representations of value that function as a medium of exchange, a unit of account, and/or a store of value.2 In many cases, virtual currencies are “convertible” currencies; they are not legal tender, but they have an equivalent value in real currency. In terms of value, Bitcoin is the most prominent virtual currency. As of late January 2015, one bitcoin equaled roughly $207 (though the value is volatile), and all bitcoins in circulation totaled $2.85 billion. The next largest virtual currency was Ripple ($441.4 million in aggregate), followed by Litecoin ($43.2 million), PayCoin ($37.8 million), and BitShares ($24.2 million). Note that despite what seems to be a tremendous interest in virtual currencies, their overall value is still extremely small relative to other payment mechanisms, such as cash, checks, and credit and debit cards. For example, in 2013, U.S. credit and debit cards accounted for over $4 trillion in spending.3

For Bitcoin, the landscape also includes virtual currency exchangers (including Coinbase and Bitstamp), as well as wallet providers (such as Coinbase, Coinkite, and BitAddress) that hold the bitcoins until they are converted or otherwise transferred. Then, there are intermediaries such as BitPay, which provide the technology and services to merchants that accept bitcoins in exchange for goods and services. Of course, these merchants are also important participants; according to recent estimates, there are now over 100,000 merchants around the world that accept Bitcoin.4 That is still a small number, but many large, high-profile companies such as Overstock, Dell, and Microsoft now accept Bitcoin, and it seems likely the number of merchants that accept virtual currency (Bitcoin in particular) will increase.

Compliance Risk

Considering the virtual currency landscape, what important risks should community bankers consider? The most significant is compliance risk, a subset of legal risk. Specifically, virtual currency administrators or exchangers may present risks similar to other money transmitters, as well as presenting their own unique risks. Quite simply, many users of virtual currencies do so because of the perception that transactions conducted using virtual currencies are anonymous. The less-than-transparent nature of the transactions may make it more difficult for a financial institution to truly know and understand the activities of its customer and whether the customer’s activities are legal. Therefore, these transactions may present a higher risk for banks and require additional due diligence and monitoring.

More technically, the U.S. Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) has designated virtual currency exchanges and administrators as money transmitters.5 Accordingly, banks are expected to manage the risks associated with the accounts of virtual currency administrators and exchanges just as they would any other money transmitter. The Bank Secrecy Act/Anti-Money Laundering (BSA/AML) Examination Manual,6 maintained and published by the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC), contains a more detailed discussion of customer due diligence and enhanced due diligence expectations, including for money transmitter customers.

Reputational Risk

Another important risk for community banks to consider is reputational risk. The February 2014 failure of Mt. Gox, the largest Bitcoin exchange and wallet provider at the time, illustrates how a bank’s reputation can be damaged because of the activities of its customers. In this case, Mt. Gox failed after losing more than $400 million of its customers’ bitcoins. Clearly, Mt. Gox did not have sufficient controls in place to ensure the bitcoins were secure. Since then, multiple lawsuits have been filed against Mt. Gox, with several also naming Mt. Gox’s bank as a defendant. Although the bank never held the bitcoins, it did handle Mt. Gox’s transactional banking needs. At least one of the lawsuits claims that the bank should have known about the fraud and that the bank profited from the fraud.

In addition to any impact to the bank’s reputation resulting from its relationship with a failed virtual currency firm, there is also the potential legal and financial impact if the bank settles or loses any of these lawsuits.

Credit Risk

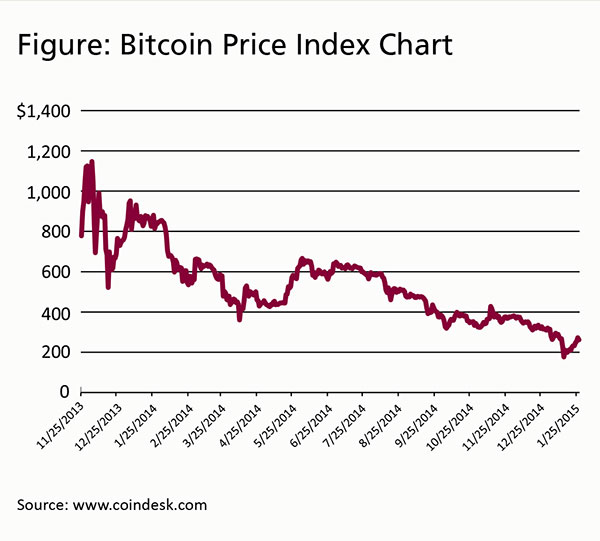

How should a community bank respond if a borrower wants to specifically post bitcoins or another virtual currency as collateral for a loan? For many, virtual currencies are simply another form of cash, so it is not hard to imagine that bankers will face such a scenario at some point. In this case, caution is appropriate. Bankers should carefully weigh the pros and cons of extending any loan secured by bitcoins or other virtual currencies (in whole or in part), or where the source of loan repayment is in some way dependent on the virtual currency. For one, the value of a bitcoin in particular has been volatile. The figure at right shows the dollar value of one bitcoin from November 25, 2013, to January 25, 2015. Thus, the collateral value could fluctuate widely from day to day. Bankers also need to think about control over the account. How does a banker control access to a virtual wallet, and how can it limit or control the borrower’s access to the virtual wallet? In the event of a loan default, the bank would need to take control of the virtual currency. This will require access to the borrower’s virtual wallet and private key. All of this suggests that the loan agreement needs to be carefully crafted and that additional steps need to be taken to ensure the bank has a perfected lien on the virtual currency.

Operational Risk

What if the bank actually owns the virtual currency? For example, it is possible a bank could find itself acquiring virtual currency in satisfaction of debts previously contracted. The most likely scenario in which this could occur is when a bank makes a business loan secured by the borrower’s business assets, which at default include virtual currency. At the moment, such a scenario is unlikely, but its plausibility increases as virtual currency becomes more mainstream.

Holding virtual currency presents some operational challenges for a financial institution. The virtual currency acquired in this manner should certainly be liquidated in an orderly fashion, but before that happens, the institution will need to have internal controls in place to mitigate the risk of loss. Management should establish dual control and access processes, as well as think about how this asset will be valued and accounted for on its financial statements. Management will also have to consider the security of the virtual currency itself, how it is held, and how vulnerable it is to theft.

Conclusion

Virtual currencies bring with them both opportunities and challenges, and they are likely here to stay. Although it is still too early to determine just how prevalent they will be in the coming years, we do expect that the various participants in the virtual currency ecosystem will increasingly intersect with the banking industry. Banks need not turn away this business as a class, but they should consider the risks of each individual customer. This will require bank management to broadly understand all the risks involved with conducting banking with these businesses. However, the risk will vary significantly depending on the specific nature of the business, and in many cases, bank management teams may correctly determine that the risk is no more significant than the risk presented by any other customer. In other situations though, the risk may be heightened and require additional due diligence, ongoing monitoring, or establishment of additional controls to appropriately manage and control the risk.

Additional Resources

The Federal Reserve’s Ask the Fed program is an excellent resource for additional information about virtual currencies. In July 2014, the Fed held two sessions on Bitcoin Payments. These sessions focused on the transactional process of virtual currencies and included a discussion of exchanges, mining, wallets, and storage. The second set of sessions, held on September 17 and November 10, 2014, focused solely on BSA/AML compliance issues related to virtual currency. Community bankers can register to access the archived versions of these presentations by visiting www.askthefed.org.

Back to top

- 1 Bitcoin and the other more recent virtual currencies are all examples of decentralized systems that allow for exchanges of value without the intermediation of a third party, are not owned or run by anyone, and operate on peer-to-peer networks. There have also been other types of centralized virtual currencies, such as the now-defunct Liberty Reserve and E-gold and the still-operating WebMoney. Centralized virtual currencies are characterized by a central clearing and access system usually owned and operated by a single administrator. For purposes of this article, virtual currency refers to decentralized virtual currencies, such as Bitcoin.

- 2 Internal Revenue Service, Notice 2014-21, March 25, 2014, available at www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-14-21.pdf.

- 3 See The Nilson Report, February 18, 2014.

- 4 Anthony Cuthbertson, “Bitcoin Now Accepted by 100,000 Merchants Worldwide,” International Business Times, February 4, 2015.

- 5 Specifically, FinCEN stated in 2013 guidance that “an administrator or exchanger that (1) accepts and transmits a convertible virtual currency or (2) buys or sells convertible virtual currency for any reason is a money transmitter under FinCEN’s regulations, unless a limitation to or exemption from the definition applies to the person.” See Department of the Treasury, Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, FIN-2013-G001, “Application of FinCEN’s Regulations to Persons Administering, Exchanging, or Using Virtual Currencies,” March 18, 2013, available at www.fincen.gov/statutes_regs/guidance/pdf/FIN-2013-G001.pdf.

- 6 See www.ffiec.gov/bsa_aml_infobase/pages_manual/manual_online.htm.